The Key to Success in Teaching: Effective Feedback Design

Among the most crucial elements of learning are capturing students’ attention, empowering them to take responsibility for active learning, promoting intermittent repetition, and providing effective feedback. So, how can feedback be designed to enhance learning effectively?

The design of teaching processes and effective teaching methods has always been a subject of constant research and curiosity. While social science fields such as philosophy, sociology, and psychology have focused on the more abstract and conceptual framework of learning, fields such as psychiatry, medicine, and neuroscience have concentrated on the physiological characteristics of learning. Today, the development of neuroscience and brain studies provides us with the opportunity to evaluate learning and teaching processes from a more holistic perspective.

Recent neuroscience research shows that individuals’ cognitive schemas are intertwined with affective features in decision-making and learning processes (Restrepo, 2014). This finding suggests that cognitive features in learning processes should be accompanied by affective features such as desire, determination, a positive attitude, value, self-efficacy, and active participation. Another important dimension of the effective teaching process that aligns with both cognitive and affective processes is feedback. Feedback assumes important functions to increase students' awareness of their deficiencies, mistakes, positive and negative attitudes and behaviors, and to improve their self-efficacy and self-regulation skills. Especially directive, corrective, and detailed feedback contributes positively to students' learning performances by enhancing their metacognitive skills and affective characteristics.

Feedback processes can be analyzed under three dimensions: cognitive, affective, and managerial. While the cognitive dimension covers basic cognitive skills at the level of comprehension, understanding, and analyzing the learning content of the feedback, the metacognitive dimension focuses on skills such as creativity, critical thinking, problem-solving, research, and decision-making. Affective characteristics such as motivation, attitude, and self-efficacy perception, which are the main sources of the learning process, show that feedback is not limited to cognitive processes but is also an important part of the learning process from an affective perspective.

In feedback processes, the feedback provided by the teacher, peers, and the student themselves are generally prominent as sources. In educational environments, feedback is mainly given by teachers. Research shows that teacher feedback is more easily accepted by students. This can be explained by the cultural dynamics of societies and the role of teachers in the curriculum implementation process. However, peer feedback accompanying teacher feedback and automatic feedback supported by artificial intelligence have a more significant impact on learning characteristics. These simultaneous or asynchronous feedbacks, provided in face-to-face and distance education designs, positively improve students’ cognitive skills, as well as their metacognitive and affective characteristics.

On the other hand, giving feedback to peers, as well as receiving feedback from peers, contributes to cognitive processes. Giving feedback can contribute to the development of students’ critical thinking skills, making objective evaluations, reviewing their own knowledge schemes, and transforming their theoretical knowledge into practical skills (Nicol et al., 2014).

It is not always possible to expect that feedback-based interaction between students will invariably improve their cognitive characteristics (Ertmer et al., 2007). The most significant difference between peer feedback and teacher feedback is the possibility that the feedback provided by peers may be inaccurate or incomplete because peers are not field experts. Some studies show that students accept feedback from teachers as unconditionally correct, whereas they act hesitantly towards feedback from peers (Gielen et al., 2010). Although there is still a need to investigate the cultural dimension of this process, studies have indicated that students tend to respond positively to positive feedback from their peers and negatively to negative feedback, and that this tendency stands out in both voting and expressions of appreciation (Weinberg et al., 2021). This situation also suggests that subjective elements may be involved in the acceptance and evaluation of peer feedback. Therefore, teachers play an important role in organizing peer feedback. Designing the feedback process transparently and having clear and understandable evaluation criteria will make it easier for students to make more objective evaluations of both their own work and the work of their peers.

The Effect of Cognitive and Affective Feedback on Learner Behavior

Feedback can focus on positive and negative behaviors in terms of cognitive and affective characteristics. The effect of positive or negative feedback on learning products or student performance may vary depending on factors such as learner characteristics, age status, type, time, and method of feedback. Based on research on feedback processes, the feedback classification system specified in the “Feedback Classification System” table below can be used regarding the direction of feedback and the possible effects it may create:

Affective Feedback |

|||

| + | - | ||

| Cognitive Feedback |

+ | ++ | +- |

| - | -+ | -- | |

The Effect of Cognitive and Affective Feedback on Learner Behavior: Positive-Positive (+ +)

Positive cognitive and affective feedback can contribute positively to students’ cognitive, metacognitive, and affective characteristics. Research shows that individuals react faster to affective feedback; especially positive feedback improves learning performance and ensures the continuation of behaviors towards this, accelerating the process of accepting feedback (Pegg et al., 2022; van Duijvenvoorde et al., 2008). This positive relationship also contributes positively to the learner's self-concepts and supports their development. Within the scope of this classification, the teacher’s verbal, written, and non-verbal behaviors, along with positive and detailed feedback in a holistic manner, can positively affect learning performance.

In this kind of feedback, it is important to discuss the reasons and evidence of students’ answers and encourage them to research, rather than emphasizing only how many correct answers they have given cognitively. However, it is of great importance that the positive feedback given is consistent with student perceptions. Positive feedback provided to a student who is aware that the work they have done is not sufficient will not match with their own perception, thus reducing the reliability of the feedback given and not providing sufficient effect (Elder et al., 2022). For this reason, teachers should organize their feedback consistently with a realistic perception and encourage students in moderation.

The Effect of Cognitive and Affective Feedback on Learner Behavior: Positive-Negative (+ -)

Although cognitively positive, feedback conveyed with a negative or neutral emotional state through verbal, written, and non-verbal behaviors triggers negative emotions in the learner and may cause them to show rejection, postponement, or resistance behavior towards the feedback. Research shows that cognitive feedback supported by a positive emotional state is more effective than feedback given with a neutral emotion. Another important factor is the detail and timing of the feedback. Even if the cognitive feedback is positive, if it is not detailed or delayed for a long time, it may cause students to evaluate this feedback negatively and not benefit from it sufficiently.

The Effect of Cognitive and Affective Feedback on Learner Behavior: Negative-Positive (- +)

In this form of interaction, the teacher supports his/her cognitively prepared negative feedback (e.g., for the questions that the student answered incorrectly) with verbal, written, or non-verbal positive behaviors (e.g., “I appreciate your improvement, I believe that you will be much more successful in the next exam if you review your deficiencies by taking into account my corrections below”). Negative feedback provides students with the opportunity to see their mistakes, to realize their deficiencies, and to increase their awareness of the aspects they can improve. Negative cognitive feedback on learning performance is more effective, especially in children aged 12 years and above, when abstract thinking skills develop (van Duijvenvoorde et al., 2008). Based on this feedback, students can make predictions and develop learning strategies to complete their deficiencies. Supporting the negative feedback given cognitively with positive emotional states contributes to students’ more active participation in the learning process and encourages them to learn.

The Effect of Cognitive and Affective Feedback on Learner Behavior: Negative-Negative (- -)

Cognitive and affective negative feedback can lead to negative interaction between the teacher and the learner. Written, verbal, and non-verbal negative feedback given by the teacher can result in negative behaviors in the cognitive skills and affective characteristics of the learner, developing resistance behaviors in the learner towards receiving new feedback. In this situation, students may exhibit behaviors such as avoidance, ignoring, and rejecting feedback, and their self-concept may also be damaged.

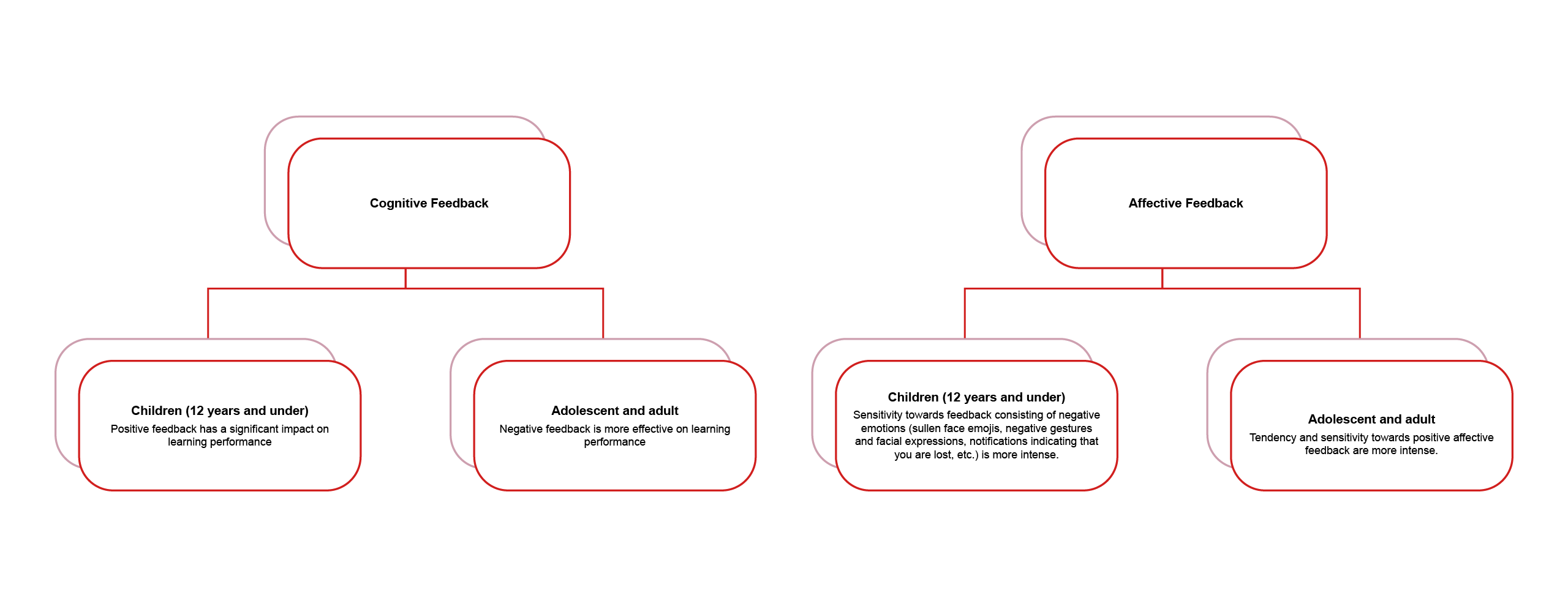

Studies show that cognitive feedback and affective feedback have different effects on learning processes depending on age characteristics (Peters et al., 2014; van Duijvenvoorde et al., 2008). Cognitively, children under the age of 12 benefit more from positive feedback, while children over the age of 12 and adults benefit more from negative feedback. The fact that the effect of feedback differs depending on the age group is also supported by developmental theory. In cognitive development theories, the fact that children over the age of 11 have cognitive complex skills, such as abstract thoughts, makes it easier for them to make inferences about negative feedback and to orientate towards the correct response (van Duijvenvoorde et al., 2008). Students’ learning behaviors towards cognitive and affective feedbacks are summarized in the figure below.

As can be seen in the figure above, this effect of cognitive feedback on students shows the opposite feature in terms of affective characteristics. Research results show that children under the age of 12 respond more neural responses to social feedback containing negative emotions (e.g., lost or angry faces) than to feedback containing positive emotions (e.g., smiley faces, emojis showing winning, etc.) (Miller et al. 2020), while adolescents and adults respond more neural responses to feedback that is emotionally supported by positive emotions (Vrtička et al. 2014).

Feedback should be included more in educational environments

As a result, feedbacks should take place more in educational environments as an important element of the learning process. Especially in today’s world where distance education opportunities have developed and artificial intelligence and internet-based technologies have entered our lives more, it is important to provide feedback by supporting it with these technologies. Although research shows that feedback is teacher-orientated, face-to-face and generally given in written form, the source, type and timing of the feedback process can be made more effective by diversifying the arrangements to be made in teacher education. The fact that effective feedback should be arranged with teacher-student-automatic resources, given instantly and intermittently in accordance with the behaviour targeted to be developed, and should include cognitive-metacognitive and affective elements gives us a clue on how feedback processes should be designed.

Bibliograpyh

- Elder, Jacob; Davis, Tyler; Hughes, Brent L. (2022): Learning About the Self: Motives for Coherence and Positivity Constrain Learning From Self-Relevant Social Feedback. In Psychological science 33 (4), pp. 629–647. DOI: 10.1177/09567976211045934

- Ertmer, P. A., Richardson, J. C., Belland, B., Camin, D., Connolly, P., Coulthard, G., Lei, K., & Mong, C. (2007). Using Peer Feedback to Enhance the Quality of Student Online Postings: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(2), 412–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00331

- Gielen, S., Peeters, E., Dochy, F., Onghena, P., & Struyven, K. (2010). Improving the effectiveness of peer feedback for learning. Learning and Instruction, 20(4), 304–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.08.007

- Miller, Jonas G.; Shrestha, Sharon; Reiss, Allan L.; Vrtička, Pascal (2020): Neural bases of social feedback processing and self-other distinction in late childhood: The role of attachment and age. In Cognitive, affective & behavioral neuroscience 20 (3), pp. 503–520. DOI: 10.3758/s13415-020-00781-w.

- Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane‐Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self‐regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199-218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090

- Pegg, Samantha; Lytle, Marisa N.; Arfer, Kodi B.; Kujawa, Autumn (2022): The time course of reactivity to social acceptance and rejection feedback: An examination of event-related potentials and behavioral measures in a peer interaction task. In Psychophysiology 59 (7), e14007. DOI: 10.1111/psyp.14007

- Peters, Sabine; Braams, Barbara R.; Raijmakers, Maartje E. J.; Koolschijn, P. Cédric M. P.; Crone, Eveline A. (2014): The neural coding of feedback learning across child and adolescent development. In Journal of cognitive neuroscience 26 (8), pp. 1705–1720. DOI: 10.1162/jocn_a_00594. Publication bibliography

- Restrepo, G. (2014). Émotion, cognition et action motivée: une nouvelle vision de la neuroéducation. Neuroeducation, 3(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.24046/neuroed.20140301.10

- van Duijvenvoorde, Anna C. K.; Zanolie, Kiki; Rombouts, Serge A. R. B.; Raijmakers, Maartje E. J.; Crone, Eveline A. (2008): Evaluating the negative or valuing the positive? Neural mechanisms supporting feedback-based learning across development. In The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 28 (38), pp. 9495–9503. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1485-08.2008.

- Vrtička, P., Sander, D., Anderson, B., Badoud, D., Eliez, S., & Debbané, M. (2014). Social feedback processing from early to late adolescence: Influence of sex, age, and attachment style. Brain and Behavior, 4(5),703–720. doi: 10.1002/brb3.251

- Weinberg, Anna; Ethridge, Paige; Pegg, Samantha; Freeman, Clara; Kujawa, Autumn; Dirks, Melanie A. (2021): Neural responses to social acceptance predict behavioral adjustments following peer feedback in the context of a real-time social interaction task. In Psychophysiology 58 (3), e13748. DOI: 10.1111/psyp.13748.

*Prof., Anadolu University; Resident Fellow, Canada-Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM), [email protected]; [email protected].